Diego Garcia and the Chagos Dispute: When Decolonization Collides With Alliance Power

The Chagos Islands/Diego Garcia dispute has re-emerged as a live, high-stakes transatlantic issue because it sits at the intersection of (1) unfinished decolonization, (2) the legal durability of the West’s most operationally valuable Indian Ocean base, and (3) the Trump administration’s broader posture: extracting leverage from allies by reframing sovereignty questions as “security questions.” The immediate trigger for the UK–US friction in January 2026 was President Trump’s public attack on the UK–Mauritius sovereignty transfer deal—despite the deal having previously been treated as supportive of US basing interests—forcing Downing Street into a defensive posture at home and abroad.

What follows is an intelligence-style political assessment: the history, the legal mechanics, the strategic and domestic incentives on both sides, the key failure modes, and where this is most likely heading as of 26 January 2026.

Key Judgements

The UK’s core objective is “legal certainty for Diego Garcia,” not “strategic retreat.” London’s argument is that continuing to hold the territory as BIOT (British Indian Ocean Territory) exposes the base to escalating international legal and diplomatic attack, which could eventually translate into operational risk (access, overflight, port calls, allied permissions) even if the base itself remains physically secure. This logic has been central to the UK Government’s case for the May 2025 UK–Mauritius agreement.

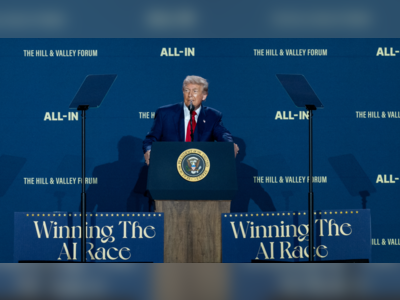

Trump’s objection is less about the text of the lease and more about control psychology and alliance signaling. The public framing—“weakness,” “stupidity,” “security risk”—aligns with a broader Trump pattern: pressuring allies by recasting negotiated legal settlements as strategic concessions. In Chagos, the substantive US interest (uninterrupted base operations) is largely protected on paper; Trump’s leverage play is about who is seen to decide.

The UK–US dispute is real, but it is structurally asymmetric: Washington needs Diego Garcia; London controls the gateway. The Chatham House analysis underscores a key point often missed in political debate: the US leases access via UK arrangements, and the current US–UK basing framework has a time horizon (commonly cited as expiring in 2036) that makes London a critical veto point in any future posture. That reality limits how far Washington can push without risking self-harm.

The most likely near-term outcome is “procedural delay, substantive continuity.” As of late January 2026, the base continues operating; the sovereignty transfer is signed but politically contested; and the implementing legislation has been delayed under parliamentary pressure after Trump’s broadside. Expect extended “legal/legislative ping-pong” and intensified UK–US technical talks, rather than abrupt reversal.

The principal strategic risk is not an immediate loss of Diego Garcia, but a slow erosion of alliance trust and a widening “sovereignty contagion.” Greenland and Chagos have become rhetorically linked in Trump’s messaging, turning discrete disputes into a single narrative: allies “failing” the US, justifying unilateralism. That is destabilizing because it invites other actors to test seams—legal seams, domestic seams, and alliance seams—rather than contesting the base directly.

Background: What Chagos/Diego Garcia Is, and Why It Never Went Away

The territorial object

The Chagos Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean. Diego Garcia is the largest and the site of a strategically central US–UK military facility that has been used for decades as an operations hub across the Middle East, South Asia, and East Africa.

The sovereignty story in one sentence

Britain detached the islands from Mauritius before Mauritius’ independence, administered them as BIOT, displaced the local population, and partnered with the United States to build Diego Garcia—then faced an accumulating international legal consensus that the decolonization process was unlawful and must be remedied.

The legal inflection point: ICJ 2019

In 2019, the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion concluding the separation of Chagos from Mauritius was wrongful under international law and that the UK should bring an end to its administration “as rapidly as possible.” While advisory opinions are not directly enforceable like judgments between states, they carry heavy normative weight and are routinely used to intensify diplomatic isolation and justify UN action.

This produced a classic strategic dilemma for London:

Option A: Keep BIOT, keep the base, accept growing legal/diplomatic pressure and the reputational and operational tail-risk.

Option B: Settle sovereignty with Mauritius in a way that locks in long-term basing rights and reduces the legal pressure.

The UK chose Option B.

The 2025 UK–Mauritius Agreement: What It Actually Does

On 22 May 2025, the UK and Mauritius signed an agreement to transfer sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius while preserving long-term operational control of Diego Garcia through a lease-back structure.

Key points (as described publicly and in official materials):

Sovereignty: Mauritius exercises sovereignty over the archipelago.

Base continuity: The UK retains rights on Diego Garcia via a long lease (commonly described as 99 years) to keep the joint facility operating.

Resettlement: Mauritius may implement resettlement on islands other than Diego Garcia; the agreement explicitly addresses resettlement provisions in the text.

Security architecture: UK officials have emphasized protective measures (exclusion zones, vetoes, constraints on foreign forces) to address concerns about hostile-state access.

Financially, UK press reporting and wire summaries cite a recurring annual lease cost figure and a large aggregate cost estimate over the lease period; these numbers are politically salient in the UK debate, though they are frequently contested in methodology and presentation.

Why the Deal Became a UK Domestic Political Flashpoint

Even if you fully accept the UK Government’s “legal certainty” logic, the deal triggers three domestic vulnerabilities:

Imperial residue + sovereignty optics

Any transfer of overseas territory is easy to frame as “giving away British land,” even when the UK’s position is legally weakened internationally. This becomes especially potent when the base is high-value and symbolic.China anxiety as a political accelerant

Opponents argue that Mauritius’ external relationships could create a pathway for Chinese influence or dual-use presence in the region. The UK position is that the agreement’s security clauses and the nature of Diego Garcia’s operation are designed specifically to prevent adversary encroachment.Chagossian consultation and legitimacy

A persistent line of critique is that displaced Chagossians were not meaningfully consulted and that any settlement should center their rights (return, compensation, community continuity). This is morally and politically powerful—because it speaks to legitimacy, not just law.

By early January 2026, the House of Lords imposed multiple defeats on the government’s Chagos-related legislative efforts (per reporting), a sign that the domestic coalition required to ratify and implement the deal is brittle.

The US Interest: What Washington Really Cares About

Stripped of rhetoric, the US priority set is straightforward:

Uninterrupted operational access (runways, port facilities, ISR, prepositioning, rapid strike capability).

Jurisdictional certainty over base operations and force protection.

Political reliability—confidence that the host framework will not become a bargaining chip in future Mauritius politics or international campaigns.

Adversary denial—assurance that neither China nor other competitors can build intelligence proximity or legal leverage around Diego Garcia.

US officials previously welcomed the 2025 agreement on the grounds that it secured “long-term, stable, and effective” operation of the joint facility. That makes Trump’s January 2026 reversal politically consequential: it suggests the issue has moved from the technical-national-security lane into the performative-leverage lane.

The January 2026 Escalation: Trump vs Starmer (How the Clash Works)

Trump’s move

According to AP and Chatham House reporting, Trump publicly attacked the UK’s Chagos policy using language like “weakness” and “stupidity,” explicitly linking it to his Greenland argument: allies “give things away,” therefore the US must act more aggressively to secure strategic geography.

This is strategically interesting because it collapses two distinct theatres into one worldview:

Greenland (Arctic, NATO, EU, North Atlantic)

Chagos/Diego Garcia (Indian Ocean, Middle East/South Asia access, decolonization law)

When a leader rhetorically ties them together, the disputes become mutually reinforcing: concession or compromise in one theatre is used as proof of vulnerability in the other.

Starmer’s bind

Starmer’s government must simultaneously:

reassure Washington that Diego Garcia remains secure,

maintain credibility with Mauritius and the UN-centered legal order,

survive UK parliamentary headwinds,

and avoid appearing to be “bullied” into reversal by a US president.

AP reports this became a direct rebuff to Starmer’s attempt to smooth broader transatlantic tensions.

What “The 1966 Treaty Problem” Actually Means

In January 2026, multiple outlets reported that peers and critics raised concerns the Chagos implementing legislation could conflict with legacy UK–US arrangements (often referenced as a 1966 framework for defense purposes). The critical point is not the precise legal citation in the press—it is the political leverage created by alleging a treaty collision:

If UK domestic actors can credibly argue the transfer breaches or complicates a US agreement, they gain a national-security veto narrative.

If US actors amplify that argument, Downing Street faces a dual-front pressure campaign: Parliament at home and Washington abroad.

This is why the government moved to delay or postpone legislative steps after Trump’s intervention, as reported by major outlets.

In intelligence terms: the treaty-collision argument is a tool for delay and renegotiation, whether or not it ultimately proves dispositive in court.

Mechanisms: How This Could Actually “Break” in Practice

It is important to be precise: losing Diego Garcia does not require an invasion or a dramatic shutdown. The real failure modes are quieter and procedural:

Ratification failure

If UK legislation stalls indefinitely, the signed agreement remains politically toxic, Mauritius remains dissatisfied, and the dispute persists. This sustains international pressure and undermines the “legal certainty” objective.Judicial review / consultation rulings

If UK courts (or political pressure) force deeper consultation with Chagossians or impose procedural conditions, it could slow or reshape implementation. That may be morally beneficial but strategically destabilizing in the short term.Mauritian domestic politics

Even with a lease, domestic pressures in Mauritius could push for symbolic assertions of sovereignty—without necessarily changing base operations, but adding friction.Adversary opportunism

Competitors do not need to “take” Diego Garcia; they can use the controversy to:

isolate the UK diplomatically,

portray the US as neo-imperial,

and incentivize regional hedging against Western basing.

Alliance trust degradation

If Washington publicly humiliates London over an issue London views as a legal necessity, it reinforces a European/UK perception that the US is a conditional ally—cooperative when convenient, coercive when transactional.

Trade-offs: The Hard Choices Each Side Is Making

UK trade-offs

Pros of the deal: reduces legal/diplomatic exposure; aligns with international law trendlines; locks in base operations through a defined framework.

Cons: domestic backlash; cost optics; accusations of strategic naïveté; procedural vulnerability around Chagossians; dependence on sustained US cooperation to keep the framework credible.

US trade-offs

Pros of endorsing the deal: continuity, legitimacy, reduced UN friction, reduced operational tail-risk.

Cons (in Trump framing): ceding “control optics,” tolerating a sovereignty narrative that challenges the post-1960s basing model, and allowing allies to claim “international law forced our hand” without extracting a price.

The “Controlled Sarcasm” Reality Check

Aphorism-style, but accurate:

“If the runway still works, the crisis is mostly political.”

“In geopolitics, the map matters—but the paperwork decides who gets to use the map.”

“Alliances don’t usually die from enemy fire; they die from friendly pressure.”

The Chagos problem is not that the base is about to vanish. The problem is that the alliance is rehearsing coercion on itself.

Current Status and Most Likely Near-Term Outcome (as of 26 Jan 2026)

Based on late-January reporting:

The sovereignty transfer agreement was signed in May 2025 and presented to Parliament.

The implementing/ratifying legislative process has faced significant House of Lords resistance and has been delayed following Trump’s public criticism.

Downing Street has publicly signaled it intends to proceed, while also managing US concerns and domestic parliamentary arithmetic.

Most likely (60–70%): continued delays, intensified UK–US technical consultations, eventual passage with amendments or political concessions that allow all sides to claim “security strengthened.”

Less likely (20–30%): formal reopening of the deal with Mauritius under US pressure, producing a revised security annex or side letters.

Low probability (10% or less): collapse of the agreement and reversion to BIOT status quo—because that reopens the international legal pressure cycle that London was trying to close.

Uncertainty acknowledgement: the decisive variable is UK domestic parliamentary management more than Washington’s rhetoric. Trump can complicate; he cannot directly ratify or block UK legislation.

Strategic Outlook: Why This Matters Beyond Chagos

Chagos has become a test case for a broader question: Can liberal alliances resolve colonial-legacy disputes in a way that preserves strategic basing without validating coercive geopolitics? If the UK successfully completes the transfer while keeping Diego Garcia fully functional, it becomes a model: sovereignty settlement plus operational continuity. If it fails amid US pressure and domestic backlash, it becomes a warning: allies cannot even legally normalize their own posture without internal fracture.

And that is why Trump rhetorically links it to Greenland: the objective is to convert legal normalization into strategic humiliation, because humiliation is leverage.

Practical Takeaways

Watch UK legislative scheduling more than headlines. Delays are the real signal.

Track whether the US shifts from rhetoric to formal demands (e.g., explicit treaty revisions tied to endorsement).

Monitor Mauritius’ public messaging: if it stays calm and technical, the deal is still alive; if it becomes nationalist, friction rises.

Pay attention to Chagossian consultation outcomes: legitimacy is the slow-burning variable that can change the deal’s survivability.

Treat “China proximity” claims carefully: they are strategically plausible as a concern, but often politically weaponized; the real question is whether the agreement’s security constraints are enforceable in practice.